Quadrophonic Landscape

Mark Iosifescu

Quadrophonic Landscapes

Leveraged Tech and Reclaimed Infrastructure in Tommy Martinez’s Distant Streams

October 21, 2025

Let’s start with the sound. Slow, an unhurried build, chorusing birdcalls and wobbles of tape delay, ocean waves shorebreaking swoony across your stereo field. Repeating, repeating, speeding and slowing, sounds arcing and echoing into directionlessness, a single immersive range being steadily demarcated around you as, inside the span, new pitches beginning to rise: a bowed guitar string, heady harmonics converted to current and compressed; low sailing bass notes, high textures on the wind; tactile synth brittleness like leaves under your feet, sampled voices flowing liquid down the panning spectrum—right to left, near to far, there and back and gone again. Before long, the feeling was one of spaciousness itself as I sat at CultureHub on a Thursday night in October, attending Tommy Martinez's performance of the fittingly-titled Distant Streams.

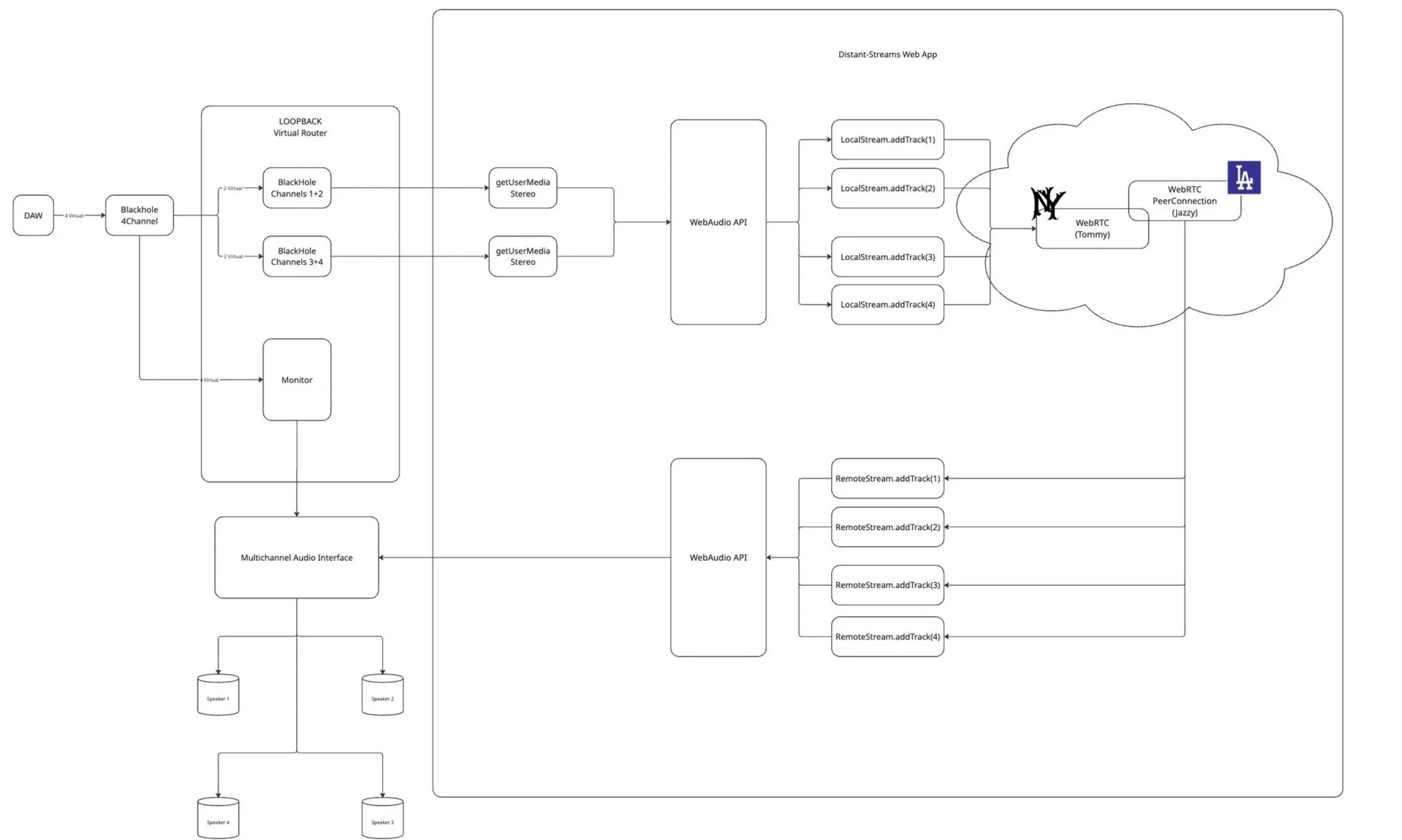

Martinez’s ongoing practice is devoted to fostering experimental possibilities in sound and music via coding: open-source software development, generative interactive systems, community-minded reorientations of the tech infrastructure that has come to dominate our world. Distant Streams, which leverages the capacities of WebRTC protocols to combine multiple remote transmissions of spatial audio, is no exception. The project uses preexisting web infrastructure—the very web technologies, in fact, that underlie our streaming and video-call-saturated day-to-day lives—to construct a new way for sound artists to collaborate.

The possibilities of Distant Streams as a tool were well represented at the system’s inaugural performance on October 2, 2025, where Martinez and the LA-based artist Jazmin “Jazzy” Romero bridged physical and conceptual space between New York and Los Angeles in ways whose complexities and dimensional subtleties went well beyond any “isn’t this cool?” kind of tech demo. Romero—whose work combines a decidedly analog outlook with multi-instrumental traditions and, increasingly, the expressive capacities of field recording—accompanied Martinez’s processed guitar work with looping cassette effects, ambient recordings, and spoken samples to create a texture richly reflective of the environmental particularities of the city from which she was transmitting.

After a series of recordings invoking layered buildups of Southern California’s natural landscapes and referencing the sonic distinctions between harmonic and dissonant intervals, the sound of Wanda Coleman’s 1985 poem “I Live for My Car”—beamed in via the recorded voice of the poet herself—had the quality of a communion among LA’s intergenerational creative lineages, of an interrogation into the human subjectivities of a life spent among alienating urban infrastructure, and of an expression of homegrown beauty crossing vast distances, whether measured in freeway offramps or continentwide fiberoptics or years and years of deliberate DIY practice and devoted artistic struggle.

Distant Streams builds on a long and storied tradition of artistic intervention into technologies that might otherwise be used only as consumer products or worse, as tools for domination. From the seminal 9 Evenings performances of 1966, to Liza Béar and Keith Sonnier’s “Send/Receive” satellite collaborations of 1977, to the telepresence experiments of Eduardo Kac and the environmental sound works of Max Neuhaus and, especially, to the long-running and extraordinary “City-Links” projects of Maryanne Amacher, artists have often acted on an impulse to counteract new tech’s otherwise bummer applications, appropriating extant machineries and directing them toward productive, communal, and homegrown, possibilities—in the best non-hierarchical, hack-the-planet sorta way.

The openness of Distant Streams allows for expressions and formations of deep nuance and referential power, drawing on the singular qualities and backgrounds of participants, locations, and networked affinities to create something greater than the sum of its technical innovations. The project’s quadraphonic possibilities offer an expanded palette for remote exchange and musical collaboration over the web—in a way that recalls Amacher’s “City-Links,” which leveraged its era’s tech infrastructure by running FM-quality recorded transmissions over dedicated phone lines. The piece also suggests a new means of reflecting on location, lineage, and other knotty time-and-space relationships.

But for me, Distant Streams’ greatest achievement is also the least summarizable. By calling on histories and prophecies of networks and kinships, traditions and formats, physical and virtual spaces all expressed via the communal gestures and utopian spaces of spirited musical collaboration, Distant Streams taps the currents that feed creation’s wellspring and carries their lessons into a living space you can feel—no idle research project or airless lecture, no workaday phone conference or video meeting, no prescriptive score or frozen recording. That which was flat lifts, expands, deepens into vividness, into full spatial expression, into irreducible multi-dimensionality.

Mark Iosifescu is a writer, musician, and editor from New York City. His writing has appeared in LCD, The Brooklyn Rail, and The Whitney Review of New Writing, and is forthcoming in n+1. He is working on a novel called The Soft Exclusion.