What is a Cloud

Katherine Yang

What is a Cloud?

Reflections on kathy wu's INTO UNCERTAIN WEATHERS

September 22, 2025

What better way to attend a performance about clouds, weather, and surveillance than to dial in remotely? I wish I could have been there in-person to appreciate Kathy Wu’s “Into Uncertain Weathers,” in that moody, balloon-filled space, but my remote experience was, in fact, perfectly fitting for the subject of the day.

Dressed in a metallic dress that matched the mylar balloons drifting through the violet space, Wu stood behind a slide projector, giving a teach-in—a brief history of “seeing the planet.” With the help of photographic slides, she mapped out points on a journey through farmers’ almanacs, systems of cloud classification, traditions of fortunetelling, surveillance interventions, and satellite imagery.

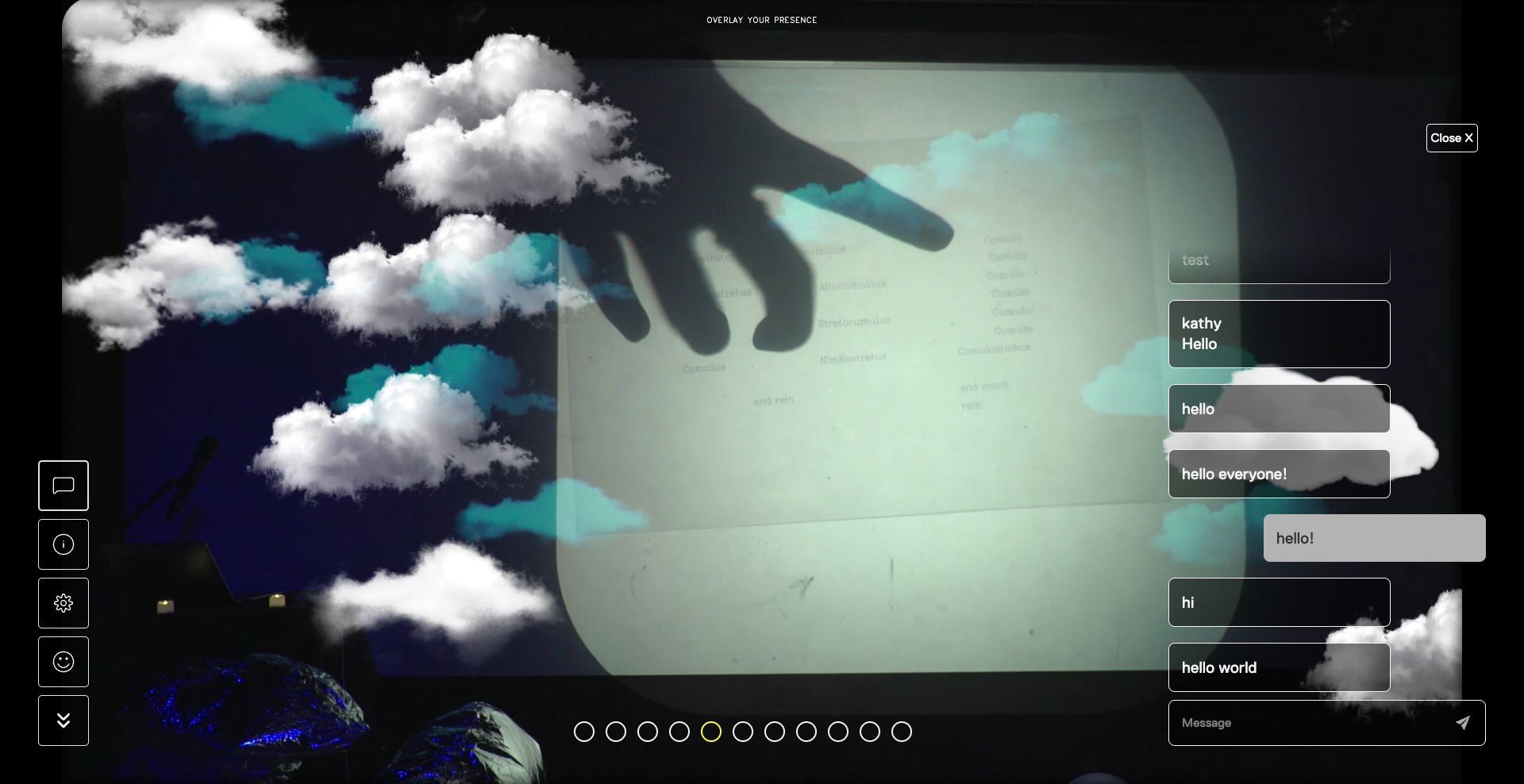

As she spoke, the dozen of us viewing online were given the opportunity to play and co-create in the performance. First, a small prompt notified us that we could annotate freely over the video stream. From an anonymous viewer, the lumpy outlines of a cloud appeared. Then, as Wu drew a tarot card—the Queen of Pentacles, representing social status, prosperity, wealth—another viewer sketched out a crown, floating above a stick figure. Next, the digital drawings were swept away and we were invited to simply “overlay our presence.” Now, our cursors controlled the placement of white, fluffy clouds. We floated around the screen, exploring the space before eventually settling into a configuration where we politely surrounded the center of the projected images.

Our clouds breathed gently in place—a sobering visual aid as Wu described Operation Popeye, a military cloud-seeding project carried out by the U.S. Air Force during the Vietnam War. In opposition, then, she guided us to consider art projects that have interrogated and intervened in institutional systems of weather and surveillance. See Hito Steyerl’s “How Not to Be Seen: A Fucking Didactic Educational .MOV File,” which asks, “How do people disappear in an age of total over-visibility? … Are people hidden by too many images? Do they go hide amongst other images? Do they become images?” See also Zhanyi Chen’s “Do Clouds Hate Weather Satellites?”, in which Chen intentionally highlights and collates the glitches in satellite images that are caused by cloud interference.

The performance culminated in a collaborative fortunetelling experience. As we submitted questions through a QR code link, our collective curiosities appeared scattered across the screen over satellite imagery—a stretched ellipse of a globe, swirling gently with the movements of the clouds.

As Wu read each question, they followed with a cryptic response that appeared on-screen.

“Why did I wake up wanting to paint clouds?” one viewer wrote in. “The Dim Time Knows,” Wu relayed. “Are we made of clouds?” wondered another viewer, to which the system proclaimed, “Accompanied by Cirrus The Clouds Warms.” In the corner of the screen, the presence of a weather forecast hinted at the underlying mechanics: the divined response was composed of a mixture of Wu’s writing and the empirical conditions of tomorrow’s weather—what could be predicted of it, at least.

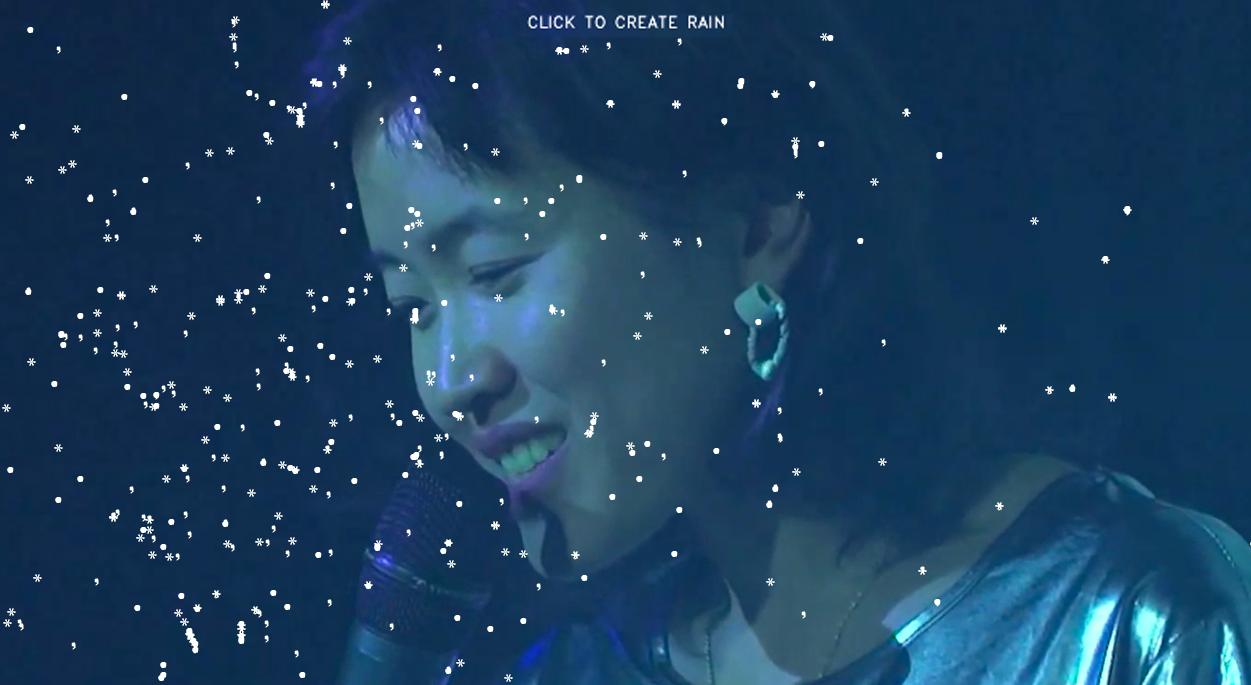

But Wu wasn’t interested in settling for plain, legible fortunetelling. She turned the clock forward, so that we were now drawing from forecasts of a few days or a week from now. We continued to solicit the universe for our fortunes, but what we received now was irregular. Every other word in a response appeared blurry or even dissolved, like weather being hard to pin down, like clouds silently resisting surveillance and authoritativeness. Those of us online were again invited to interact, this time by clicking to create rain, further occluding the fortune with a torrent of commas, apostrophes, circles, and asterisks.

To draw the session to a close, Wu called on the online viewers to find their way to the center of the sky (or try their best to do so, technical difficulties notwithstanding). My cursor felt proud and weighty with significance. As I moved my little black pointer to join the others, I imagined the physical travel necessary for this near-instantaneous transmission of my presence—through the movement of my hand on my mouse, through the computational layers of my computer, through all the layers of our infrastructure, to arrive a couple hundred miles to the space there in New York, where attendees in-person watched the cursors congregate. Perhaps, right in the middle of it all, data was being transmitted through a satellite in orbit, passing through the clouds each way, up to the stratosphere and back down to earth—countless times over the course of the hour.

“What is a cloud?” a viewer had asked, starting with the basics. A cloud is many things, as Wu thoroughly explored—it’s daily life; it’s science fiction; it’s magic; it’s warfare; it’s arguably part of an overly rigid system of classification that a German Romantic painter might decry. Mainly, though, it’s a feeling of comfort and encouragement that I was feeling by the end of Wu’s performance. It’s that, in many ways, even as the computational Cloud governs me in my digital life, the clouds of the sky hold me and protect me and humble me, and perhaps can teach me about how we might all disappear, finding peace in subversive concealment.

Katherine Yang is an artist and programmer working with language, code, and interfaces. In particular, she is dedicated to exploring soft tech and poetic tools. Her work has appeared in Pleiades, Taper, The HTML Review, Electronic Literature Organization, and Backslash Lit. She currently works as a developer and designer at Fathom Information Design in Boston, and enjoys knitting and indie video games in her free time.